The snow is falling, the semester is winding down, and everyone’s looking forward to a break. It’s been a very busy year for the Bates Fluids group, and I’m excited to announce that in the past few weeks, we’ve had three (!!) papers accepted, including one featuring group member Morgan Baxter (Bates ‘20). The vast range of topics these papers cover, from biofilm growth to the stability of rotating plasmas to the flexible numerical methods we work on, speaks to the extremely broad applicability of fluid dynamics! These applications range from scales of microns to megameters and everything in between.

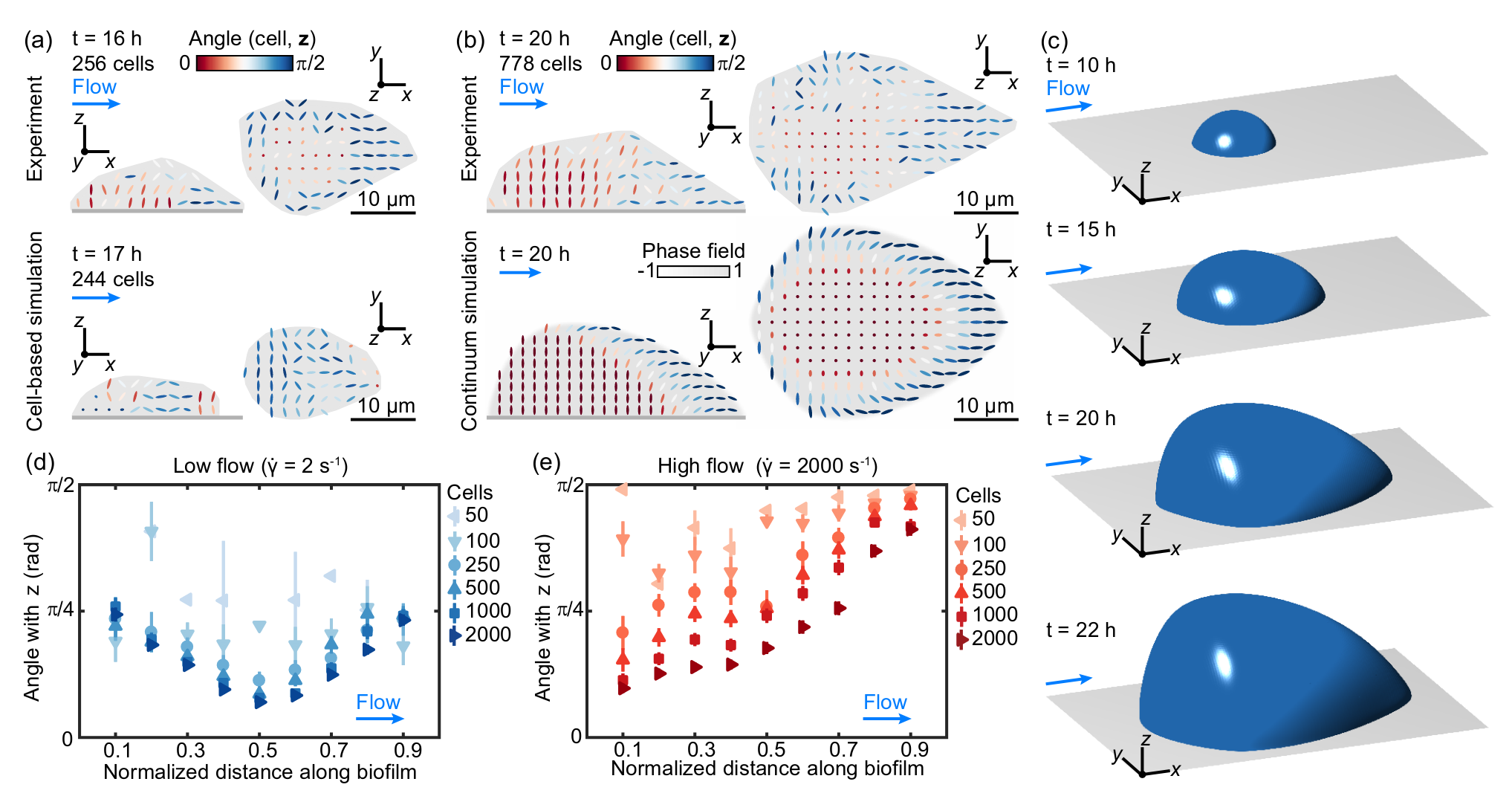

First, our first biophysics paper has been accepted to Physical Review Letters (a preprint is available at BiorXiv). In this work, we constructed a multi-scale model for biofilms growing in shear flows. Biofilms are ubiquitous assemblages of microorganisms stuck together by an extracellular matrix, often growing on a surface. They are found in pipelines, in medical devices, and in human organs. In nearly all of these environments, biofilms grow in the presence of strong shear flows. Using experimental data from our collaborators in Marburg, we developed a continuum (e.g. fluid) model for a fluid with growth-induced activity. While on leave last fall at MIT Mathematics, I helped develop an active phase-field model and implement it in Dedalus with Phil Pearce and Dominic Skinner. We were able to successfully match experimental data using a model in which the shape of the biofilm is initially determined by deformation of individual cells by the flow but evolves into a configuration in which the vertical growth of cells in center of the film determines the overall shape at later times. In the figure below, you can see a “wave” of verticalization, driven by the fact that the cells in the center of the biofilm are shielded from the flow and “buckle” upwards when they try to grow on the surface.

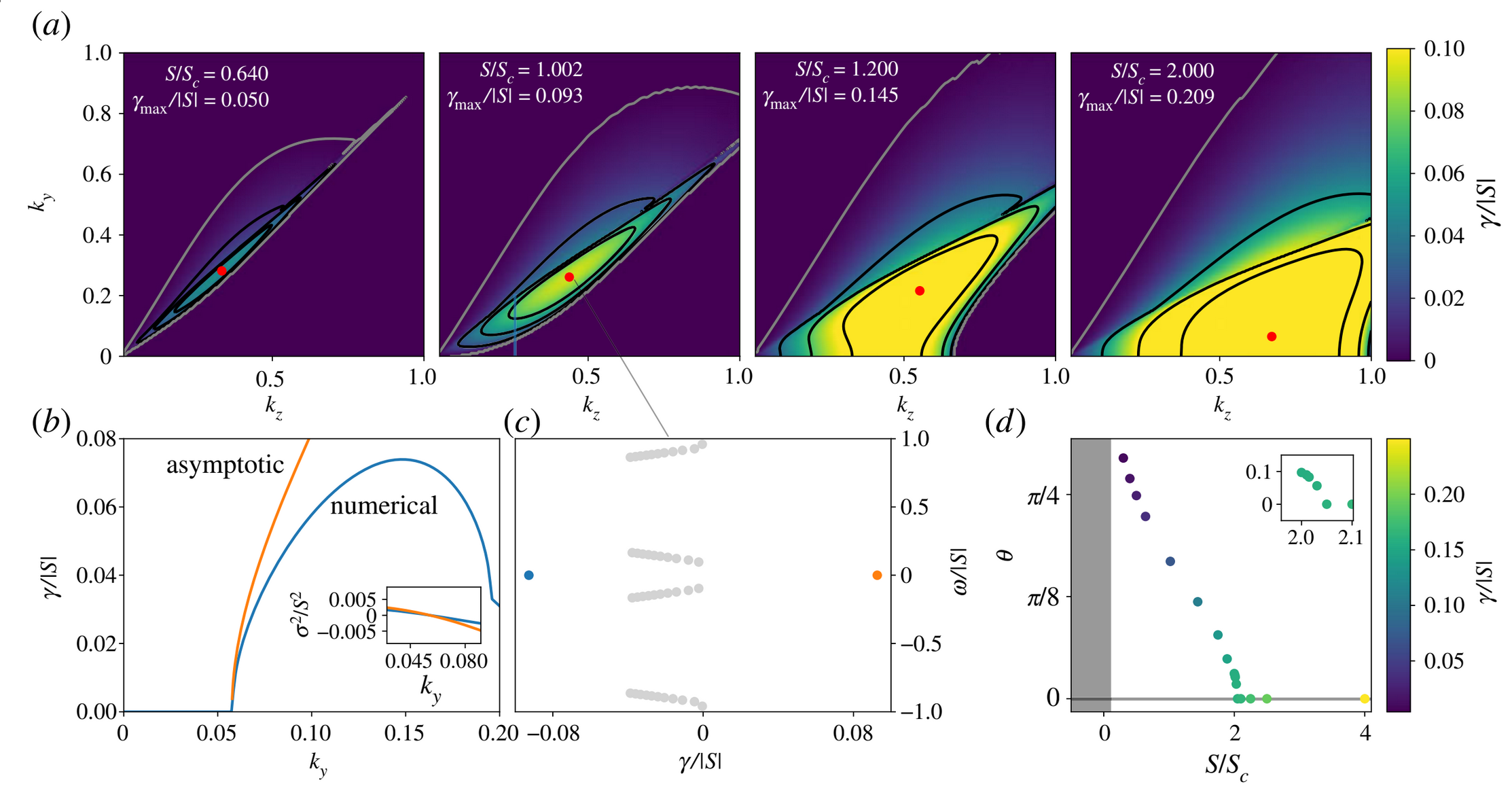

Our paper on the three-dimensional magnetorotational instability accepted to Proceedings of the Royal Society A (the preprint is available on arxiv). In this work, Morgan Baxter (Bates ‘20) performed dozens of linear stability calculations of the magnetorotational instability (MRI), an extremely important process in astrophysics. The MRI occurs when a rotating, electrically conducting fluid has angular velocity decreasing with distance from the center of rotation in the presence of a weak magnetic field. Such a setup triggers a violent instability that can transport angular momentum outwards, which makes it very important in the theory of accretion disks, where material falls inwards into a central object. However, we are interested in the potential for the MRI to act in a very different context: in the outer layers of the Sun and in liquid metal experiments on Earth. In both of these contexts, the MRI is not driven strongly but is weakly unstable. In this regime, it turns out that the most unstable structures are three dimensional, rather than two-dimensional, as had previously been thought. This is very important, because it raises the possibility that such weakly unstable (technically called “weakly nonlinear systems”) may be able to amplify magnetic fields. Systems that dynamically generate their own magnetic field, rather than relying on a field that was implanted in the object by an external process, are called dynamos. The Sun and Earth are both famous examples of dynamos; in the case of the Sun, the field regenerates itself on an 11 year cycle. This paper lays the groundwork for a new theory of solar dynamos in which the weakly non-linear MRI generates the field. One of the most exciting parts of this paper was the very nice agreement between the numerical computations Morgan performed and the analytic theory work by Geoff Vasil and me, which can be seen in panel the figure below.

Finally, I’m extremely excited to announce that the long-awaited paper describing the Dedalus Project has finally been accepted in the brand-new journal Physical Review Research (the preprint is up on arxiv). This paper, which is a mere 37 pages long in its preprint version, details nearly every aspect of the code, including its mathematical underpinnings, its custom computer algebra system that turns text equations into maximally sparse matrices, and much more. One of the most exciting parts, particularly if you’re not interested in the details of sparse, parallel, pseudospectral numerical methods, is the extensive gallery of example problems, ranging from classic Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities to the diamagnetic levitation of frogs (yes, really). Best of all, we have posted all the code for every example, including plot scripts. This way, you can get started on your own problems by hacking the example nearest to your area of interest! Congratulations especially to Keaton Burns, who started working on Dedalus as an undergraduate with me back in 2011, continued all through his graduate work at Cambridge and MIT, and continues to be the project leader as an Instructor in the MIT Math department. You can find a feature on the early days of the Dedalus Collaboration on page 4 of the Fall issue of Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics Newsletter.

Here’s looking forward to a 2020 filled with many more exciting projects!